Indexing and Hashing:Dynamic Hashing.

Dynamic Hashing

As we have seen, the need to fix the set B of bucket addresses presents a serious problem with the static hashing technique of the previous section. Most databases grow larger over time. If we are to use static hashing for such a database, we have three classes of options:

1. Choose a hash function based on the current file size. This option will result in performance degradation as the database grows.

2. Choose a hash function based on the anticipated size of the file at some point in the future. Although performance degradation is avoided, a significant amount of space may be wasted initially.

3. Periodically reorganize the hash structure in response to file growth. Such a reorganization involves choosing a new hash function, recomputing the hash function on every record in the file, and generating new bucket assignments. This reorganization is a massive, time-consuming operation. Furthermore, it is necessary to forbid access to the file during reorganization.

Several dynamic hashing techniques allow the hash function to be modified dynamically to accommodate the growth or shrinkage of the database. In this section we describe one form of dynamic hashing, called extendable hashing. The bibliographical notes provide references to other forms of dynamic hashing.

Data Structure

Extendable hashing copes with changes in database size by splitting and coalescing buckets as the database grows and shrinks. As a result, space efficiency is retained. Moreover, since the reorganization is performed on only one bucket at a time, the resulting performance overhead is acceptably low.

With extendable hashing, we choose a hash function h with the desirable properties of uniformity and randomness. However, this hash function generates values over a relatively large range—namely, b-bit binary integers. A typical value for b is 32.

We do not create a bucket for each hash value. Indeed, 232 is over 4 billion, and that many buckets is unreasonable for all but the largest databases. Instead, we create buckets on demand, as records are inserted into the file. We do not use the entire b bits of the hash value initially. At any point, we use i bits, where 0 ≤ i ≤ b. These I bits are used as an offset into an additional table of bucket addresses. The value of I grows and shrinks with the size of the database.

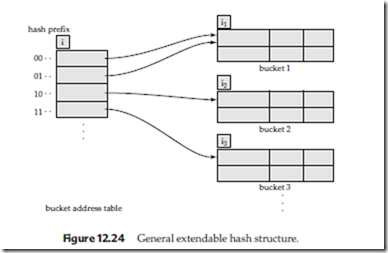

Figure 12.24 shows a general extendable hash structure. The i appearing above the bucket address table in the figure indicates that i bits of the hash value h(K) are required to determine the correct bucket for K. This number will, of course, change as the file grows. Although i bits are required to find the correct entry in the bucket address table, several consecutive table entries may point to the same bucket. All such entries will have a common hash prefix, but the length of this prefix may be less than i. Therefore, we associate with each bucket an integer giving the length of the common hash prefix. In Figure 12.24 the integer associated with bucket j is shown as ij . The number of bucket-address-table entries that point to bucket j is

Queries and Updates

We now see how to perform lookup, insertion, and deletion on an extendable hash structure.

To locate the bucket containing search-key value Kl, the system takes the first i high-order bits of h(Kl), looks at the corresponding table entry for this bit string, and follows the bucket pointer in the table entry.

To insert a record with search-key value Kl, the system follows the same procedure for lookup as before, ending up in some bucket—say, j. If there is room in the bucket, the system inserts the record in the bucket. If, on the other hand, the bucket is full, it must split the bucket and redistribute the current records, plus the new one. To split the bucket, the system must first determine from the hash value whether it needs to increase the number of bits that it uses.

• If i = ij , only one entry in the bucket address table points to bucket j. There- fore, the system needs to increase the size of the bucket address table so that it can include pointers to the two buckets that result from splitting bucket j. It does so by considering an additional bit of the hash value. It increments the value of i by 1, thus doubling the size of the bucket address table. It replaces each entry by two entries, both of which contain the same pointer as the orig- inal entry. Now two entries in the bucket address table point to bucket j. The system allocates a new bucket (bucket z), and sets the second entry to point to the new bucket. It sets ij and iz to i. Next, it rehashes each record in bucket j and, depending on the first i bits (remember the system has added 1 to i), either keeps it in bucket j or allocates it to the newly created bucket.

The system now reattempts the insertion of the new record. Usually, the attempt will succeed. However, if all the records in bucket j, as well as the new record, have the same hash-value prefix, it will be necessary to split a bucket again, since all the records in bucket j and the new record are assigned to the same bucket. If the hash function has been chosen carefully, it is unlikely that a single insertion will require that a bucket be split more than once, unless there are a large number of records with the same search key. If all the records in bucket j have the same search-key value, no amount of splitting will help. In such cases, overflow buckets are used to store the records, as in static hashing.

• If i > ij , then more than one entry in the bucket address table points to bucket j. Thus, the system can split bucket j without increasing the size of the bucket address table. Observe that all the entries that point to bucket j correspond to hash prefixes that have the same value on the leftmost ij bits. The system allocates a new bucket (bucket z), and set ij and iz to the value that results from adding 1 to the original ij value. Next, the system needs to adjust the entries in the bucket address table that previously pointed to bucket j. (Note that with the new value for ij , not all the entries correspond to hash prefixes that have the same value on the leftmost ij bits.) The system leaves the first half of the entries as they were (pointing to bucket j), and sets all the remaining entries to point to the newly created bucket (bucket z). Next, as in the previous case, the system rehashes each record in bucket j, and allocates it either to bucket j or to the newly created bucket z.

The system the nreattemptstheinsert.Intheunlikelycasethatitagainfails, it applies one of the two cases, i = ij or i > ij , as appropriate.

Note that, in both cases, the system needs to recompute the hash function on only the records in bucket j.

To delete a record with search-key value Kl, the system follows the same procedure for lookup as before, ending up in some bucket—say, j. It removes both the

search key from the bucket and the record from the file. The bucket too is removed if it becomes empty. Note that, at this point, several buckets can be coalesced, and the size of the bucket address table can be cut in half. The procedure for deciding on which buckets can be coalesced and how to coalesce buckets is left to you to do as an exercise. The conditions under which the bucket address table can be reduced in size are also left to you as an exercise. Unlike coalescing of buckets, changing the size of the bucket address table is a rather expensive operation if the table is large. Therefore it may be worthwhile to reduce the bucket address table size only if the number of buckets reduces greatly.

Our example account file in Figure 12.25 illustrates the operation of insertion. The 32-bit hash values on branch-name appear in Figure 12.26. Assume that, initially, the file is empty, as in Figure 12.27. We insert the records one by one. To illustrate all the features of extendable hashing in a small structure, we shall make the unrealistic assumption that a bucket can hold only two records.

We insert the record (A-217, Brighton, 750). The bucket address table contains a pointer to the one bucket, and the system inserts the record. Next, we insert the record (A-101, Downtown, 500). The system also places this record in the one bucket of our structure.

When we attempt to insert the next record (Downtown, A-110, 600), we find that the bucket is full. Since i = i0, we need to increase the number of bits that we use from the hash value. We now use 1 bit, allowing us 21 = 2 buckets. This increase in

the number of bits necessitates doubling the size of the bucket address table to two entries. The system splits the bucket, placing in the new bucket those records whose search key has a hash value beginning with 1, and leaving in the original bucket the other records. Figure 12.28 shows the state of our structure after the split.

Next, we insert (A-215, Mianus, 700). Since the first bit of h(Mianus) is 1, we must insert this record into the bucket pointed to by the “1” entry in the bucket address table. Once again, we find the bucket full and i = i1. We increase the number of bits that we use from the hash to 2. This increase in the number of bits necessitates doubling the size of the bucket address table to four entries, as in Figure 12.29. Since the bucket of Figure 12.28 for hash prefix 0 was not split, the two entries of the bucket address table of 00 and 01 both point to this bucket.

For each record in the bucket of Figure 12.28 for hash prefix 1 (the bucket being split), the system examines the first 2 bits of the hash value to determine which bucket of the new structure should hold it.

Next, we insert (A-102, Perryridge, 400), which goes in the same bucket as Mianus. The following insertion, of (A-201, Perryridge, 900), results in a bucket overflow, lead- ing to an increase in the number of bits, and a doubling of the size of the bucket address table. The insertion of the third Perryridge record, (A-218, Perryridge, 700), leads to another overflow. However, this overflow cannot be handled by increasing the number of bits, since there are three records with exactly the same hash value. Hence the system uses an overflow bucket, as in Figure 12.30.

We continue in this manner until we have inserted all the account records of Figure 12.25. The resulting structure appears in Figure 12.31.

Comparison with Other Schemes

We now examine the advantages and disadvantages of extendable hashing, com- pared with the other schemes that we have discussed. The main advantage of extendable hashing is that performance does not degrade as the file grows. Further- more, there is minimal space overhead. Although the bucket address table incurs additional overhead, it contains one pointer for each hash value for the current pre-

fix length. This table is thus small. The main space saving of extendable hashing over other forms of hashing is that no buckets need to be reserved for future growth; rather, buckets can be allocated dynamically.

A disadvantage of extendable hashing is that lookup involves an additional level of indirection, since the system must access the bucket address table before accessing the bucket itself. This extra reference has only a minor effect on performance. Although the hash structures that we discussed in Section 12.5 do not have this ex- tra level of indirection, they lose their minor performance advantage as they become full.

Thus, extendable hashing appears to be a highly attractive technique, provided that we are willing to accept the added complexity involved in its implementation. The bibliographical notes reference more detailed descriptions of extendable hashing implementation. The bibliographical notes also provide references to another form of dynamic hashing called linear hashing, which avoids the extra level of indirection associated with extendable hashing, at the possible cost of more overflow buckets.

Comments

Post a Comment