Indexing and Hashing:Static Hashing

Static Hashing

One disadvantage of sequential file organization is that we must access an index structure to locate data, or must use binary search, and that results in more I/O operations. File organizations based on the technique of hashing allow us to avoid accessing an index structure. Hashing also provides a way of constructing indices. We study file organizations and indices based on hashing in the following sections.

Hash File Organization

In a hash file organization, we obtain the address of the disk block containing a desired record directly by computing a function on the search-key value of the record. In our description of hashing, we shall use the term bucket to denote a unit of storage that can store one or more records. A bucket is typically a disk block, but could be chosen to be smaller or larger than a disk block.

Formally, let K denote the set of all search-key values, and let B denote the set of all bucket addresses. A hash function h is a function from K to B. Let h denote a hash function.

To insert a record with search key Ki, we compute h(Ki), which gives the address of the bucket for that record. Assume for now that there is space in the bucket to store the record. Then, the record is stored in that bucket.

To perform a lookup on a search-key value Ki, we simply compute h(Ki), then search the bucket with that address. Suppose that two search keys, K5 and K7, have the same hash value; that is, h(K5) = h(K7). If we perform a lookup on K5, the bucket h(K5) contains records with search-key values K5 and records with search key values K7. Thus, we have to check the search-key value of every record in the bucket to verify that the record is one that we want.

Deletion is equally straightforward. If the search-key value of the record to be deleted is Ki, we compute h(Ki), then search the corresponding bucket for that record, and delete the record from the bucket.

Hash Functions

The worst possible hash function maps all search-key values to the same bucket. Such a function is undesirable because all the records have to be kept in the same bucket. A lookup has to examine every such record to find the one desired. An ideal hash function distributes the stored keys uniformly across all the buckets, so that every bucket has the same number of records.

Since we do not know at design time precisely which search-key values will be stored in the file, we want to choose a hash function that assigns search-key values to buckets in such a way that the distribution has these qualities:

• The distribution is uniform. That is, the hash function assigns each bucket the same number of search-key values from the set of all possible search-key values.

• The distribution is random. That is, in the average case, each bucket will have nearly the same number of values assigned to it, regardless of the actual distribution of search-key values. More precisely, the hash value will not be correlated to any externally visible ordering on the search-key values, such as alphabetic ordering or ordering by the length of the search keys; the hash function will appear to be random.

As an illustration of these principles, let us choose a hash function for the account file using the search key branch-name. The hash function that we choose must have the desirable properties not only on the example account file that we have been using, but also on an account file of realistic size for a large bank with many branches.

Assume that we decide to have 26 buckets, and we define a hash function that maps names beginning with the ith letter of the alphabet to the ith bucket. This hash function has the virtue of simplicity, but it fails to provide a uniform distribution, since we expect more branch names to begin with such letters as B and R than Q and X, for example.

Now suppose that we want a hash function on the search key balance. Suppose that the minimum balance is 1 and the maximum balance is 100,000, and we use a hash function that divides the values into 10 ranges, 1–10,000, 10,001–20,000 and so on. The distribution of search-key values is uniform (since each bucket has the same number of different balance values), but is not random. But records with balances between 1 and 10,000 are far more common than are records with balances between 90,001 and 100,000. As a result, the distribution of records is not uniform—some buckets receive more records than others do. If the function has a random distribution, even if there are such correlations in the search keys, the randomness of the distribution will make it very likely that all buckets will have roughly the same number of records, as long as each search key occurs in only a small fraction of the records. (If a single search key occurs in a large fraction of the records, the bucket containing it is likely to have more records than other buckets, regardless of the hash function used.)

Typical hash functions perform computation on the internal binary machine representation of characters in the search key. A simple hash function of this type first computes the sum of the binary representations of the characters of a key, then returns the sum modulo the number of buckets. Figure 12.21 shows the application of such a scheme, with 10 buckets, to the account file, under the assumption that the ith letter in the alphabet is represented by the integer i.

Hash functions require careful design. A bad hash function may result in lookup taking time proportional to the number of search keys in the file. A well-designed function gives an average-case lookup time that is a (small) constant, independent of the number of search keys in the file.

Handling of Bucket Overflows

So far, we have assumed that, when a record is inserted, the bucket to which it is mapped has space to store the record. If the bucket does not have enough space, a bucket overflow is said to occur. Bucket overflow can occur for several reasons:

• Insufficient buckets. The number of buckets, which we denote nB , must be chosen such that nB > nr /fr , where nr denotes the total number of records that will be stored, and fr denotes the number of records that will fit in a bucket. This designation, of course, assumes that the total number of records is known when the hash function is chosen.

• Skew. Some buckets are assigned more records than are others, so a bucket may overflow even when other buckets still have space. This situation is called bucket skew. Skew can occur for two reasons:

1. Multiple records may have the same search key.

2. The chosen hash function may result in nonuniform distribution of search keys.

So that the probability of bucket overflow is reduced, the number of buckets is chosen to be (nr /fr ) ∗ (1 + d), where d is a fudge factor, typically around 0.2. Some space is wasted: About 20 percent of the space in the buckets will be empty. But the benefit is that the probability of overflow is reduced.

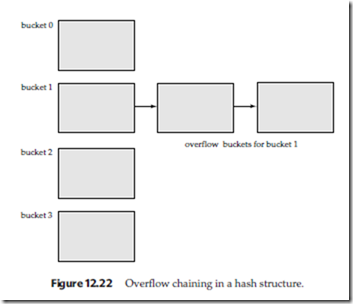

Despite allocation of a few more buckets than required, bucket overflow can still occur. We handle bucket overflow by using overflow buckets. If a record must be inserted into a bucket b, and b is already full, the system provides an overflow bucket for b, and inserts the record into the overflow bucket. If the overflow bucket is also full, the system provides another overflow bucket, and so on. All the overflow buck-

ets of a given bucket are chained together in a linked list, as in Figure 12.22. Overflow handling using such a linked list is called overflow chaining.

We must change the lookup algorithm slightly to handle overflow chaining. As before, the system uses the hash function on the search key to identify a bucket b. The system must examine all the records in bucket b to see whether they match the search key, as before. In addition, if bucket b has overflow buckets, the system must examine the records in all the overflow buckets also.

The form of hash structure that we have just described is sometimes referred to as closed hashing. Under an alternative approach, called open hashing, the set of buckets is fixed, and there are no overflow chains. Instead, if a bucket is full, the sys- tem inserts records in some other bucket in the initial set of buckets B. One policy is to use the next bucket (in cyclic order) that has space; this policy is called linear probing. Other policies, such as computing further hash functions, are also used. Open hashing has been used to construct symbol tables for compilers and assemblers, but closed hashing is preferable for database systems. The reason is that deletion un- der open hashing is troublesome. Usually, compilers and assemblers perform only lookup and insertion operations on their symbol tables. However, in a database sys- tem, it is important to be able to handle deletion as well as insertion. Thus, open hashing is of only minor importance in database implementation.

An important drawback to the form of hashing that we have described is that we must choose the hash function when we implement the system, and it cannot be changed easily thereafter if the file being indexed grows or shrinks. Since the function h maps search-key values to a fixed set B of bucket addresses, we waste space if B is made large to handle future growth of the file. If B is too small, the buckets contain records of many different search-key values, and bucket overflows can occur. As the file grows, performance suffers. We study later, in Section 12.6, how the number of buckets and the hash function can be changed dynamically.

Hash Indices

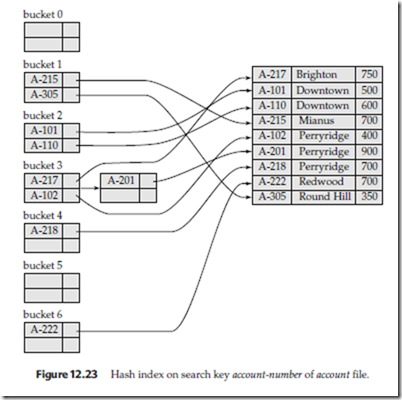

Hashing can be used not only for file organization, but also for index-structure creation. A hash index organizes the search keys, with their associated pointers, into a hash file structure. We construct a hash index as follows. We apply a hash function on a search key to identify a bucket, and store the key and its associated pointers in the bucket (or in overflow buckets). Figure 12.23 shows a secondary hash index on the account file, for the search key account-number. The hash function in the figure computes the sum of the digits of the account number modulo 7. The hash index has seven buckets, each of size 2 (realistic indices would, of course, have much larger

bucket sizes). One of the buckets has three keys mapped to it, so it has an overflow bucket. In this example, account-number is a primary key for account, so each search- key has only one associated pointer. In general, multiple pointers can be associated with each key.

We use the term hash index to denote hash file structures as well as secondary hash indices. Strictly speaking, hash indices are only secondary index structures. A hash index is never needed as a primary index structure, since, if a file itself is organized by hashing, there is no need for a separate hash index structure on it. However, since hash file organization provides the same direct access to records that indexing provides, we pretend that a file organized by hashing also has a primary hash index on it.

Comments

Post a Comment